Scratch Cooking

Why Scratch Cooking?

Many schools and community orgs choose to purchase bulk food and cook on site. Scratch cooking has many benefits over purchasing vended meals:

Cost-effective

Tailor menus to student preferences

Create food service jobs at school

Ability to source from local farms and manufacturers

Read more: What is Scratch Cooking?

What are food values?

Food values are the beliefs that underpin a school food program.

Nutrition philosophy: describes approach to menu planning and food services, including why and how a school/district chooses to serve kids

Ingredient guide: lists ingredients that are encouraged, avoided, and prohibited, and a rationale

Food Values

Why document food values?

Guide decision-making: Talking about food—and what is considered “good food”—is deeply personal, and personal values about food vary widely. Even in a professional setting, it can be hard to agree on what “good food” means, especially without a science-based document to guide the conversation. Documenting a written set of food values grounds the conversation in science rather than relying on our personal beliefs to make decisions.

Transparency: Documenting food values is important for transparency. School districts are answerable to the community, and families need to understand what food is being served and why. Creating an environment in which students are ready to learn means ensuring that our children have healthy, nourished bodies—in part by serving the best food possible in schools.

Where to begin?

The USDA sets minimum guidelines for nutritional standards, but many schools find these guidelines to be not specific or far-reaching enough. Your nutritional guidelines will reflect the values and preferences of your community.

Food & Nutrition Philosophy Statement - the “what” and “why” of your food service program

Values around food production, nutrition, and child wellness.

Menu guidelines, including service models, student choice, and program core values

Food and Nutrition Ingredient Guidelines

Which ingredients are encouraged, prohibited, restricted, and permitted but monitored for future research

Includes rationale - scientific or cultural - for each item

Examples

Building a menu

Scratch cooking puts the menu at the center of the model, and part of transitioning to scratch cooking is shifting people’s thinking regarding the menu. The food that is featured on the rotating menu greatly influences decisions about kitchen equipment and design, procurement strategies, serving model, and cafeteria culture. With vended meals, the menu is often positioned as a communications tool for parents and students. While this still holds true in a scratch cooking world, the menu is so much more: it is a dataset that informs every part of the model.

The Menu

A good school food menu meets three criteria:

Affordable: the menu cycle as a whole is cost effective

Easy: recipes are easy to execute in the kitchen

Appealing: students love it!

Most menus follow a 3 to 5 week cycle that repeats for a few months before changing. Benefits of a cycle menu:

Reliable food procurement: a stable menu cycle makes it easier to project how much food to buy, and when it needs to arrive.

Easy for staff: With a predictable menu cycle, kitchen staff can master new recipes over time without having to constantly learn on the go.

Good for data collection: A key piece of kitchen ops is measuring how much food is prepared, served, and discarded. A predictable menu cycle allows time for new dishes to appear a few times to get good data on what’s working and what isn’t.

Key to many scratch cooking programs is a deconstructed menu, similar to a Sweetgreen or Chipotle restaurant, where components of the meal are served separately. This model allows for student choice. For example, a spaghetti and meatballs day may have spaghetti, tomato sauce, meatballs, cheese, and sub rolls all served separately, rather than pre-combined.

Deconstructed menus

A deconstructed menu means that entree dishes are served in discrete components, much like you would see at a Chipotle or Sweetgreen restaurant. This allows for student choice and customization, and is more efficient from a cost perspective.

For example: spaghetti and meatballs could be served as separate pans of spaghetti, meatballs, tomato sauce, sub rolls, and parmesan cheese. Students can pick any combination and have them plated per their liking, e.g. tomato sauce on the side.

Recipe Development

In order to achieve efficiency in the food procurement process, recipes and the menu must yield the most value out of the fewest ingredients, within reason.In other words, the problem is: How many unique, delicious recipes can we create from the same list of ingredients?

Successful scratch cooking programs balance four criteria:

Price: Does this recipe fall within our budget parameters?

Student acceptance: Is this recipe exciting and appealing to students?

Ease of execution and replication: Is this recipe easy enough to assemble? Will it smell, look, and taste the same wherever it is served?

Nutritional value: Is this recipe acceptable per our food values and nutritional standards?

Here are some tried-and-true sources for USDA-compliant recipes to get started. But note: it’s easy to meet the USDA criteria, so use these for inspiration but don’t feel limited.

Food procurement begins at the menu.

In order to procure food, you’ll need to build a list of which products you want to buy, and how much you want to buy of those items. Drafting a menu cycle allows you to project out your needs and estimate your costs.

Procurement

STEP 1:

Identify the major, recurring menu items.

Animal proteins tend to be used heavily - many menus use beef, chicken, and fish most frequently. As for grains, rice, pasta, and bread are most. Start by making a list of the most common menu items you expect to use.

STEP 2:

Determine how often you plan to serve those items.

When you have a list of menu items, begin to draft a menu cycle. For example, during a 20-day period, on how many days do you expect to serve beef, chicken, and fish? Repeat this process for all items identified in Step 1, not worrying too much about the actual recipes or menu applications but focusing more on categories.

STEP 3:

Project how much food you need for the year.

When you have a working cycle menu, do the math to figure out how many times throughout the school year our cycle will repeat. Compare these totals with the number of meals you expect to serve. Using these two data points you can project how much food to buy.

Bids and Requests for Proposal (RFPs)

Bids and RFPs are the mechanism by which you will procure food and maximize your district’s buying power. Usually a legal requirement for the procurement process, these are tools to help you secure the most competitive pricing on food and equipment with manufacturers and/or vendors.

There are 4 key components to developing a strong bid or RFP:

Do your research. Be sure you look into and thoroughly understand your state and city’s procurement laws—this will be important for putting your proposal together.

Consider your food values. A well-constructed RFP can help you implement cultural and policy changes that reflect your district’s values from the very beginning of the process—for example, you can specify that your food be sourced nearby and support your local workforce.

Develop a strategy. Using your research, develop a plan that will enable you to be effective, strategic, and representative of your district’s values within your state and city’s laws.

Write your bid / RFP. Refer to your city/state procurement rules for technical assistance.

Remember: Because of the strict rules attached to procurement, if you are not intentional when writing bids and RFPs, you will be limited in your ability to specify your requirements after the fact. Be sure to do the work upfront, and build in specifications based on your values and needs.

Buying direct vs. through a third party

There are two main ways to purchase food: you can buy direct from the source (e.g. from a farmer, bakery, or vegetable wholesaler), or you can buy from a third party (e.g. from a grocery vendor or a food service management company).

To determine which strategy is right for you, consider the following factors:

How much of this product do you intend to buy? Is it a large volume or small volume?

Are you able to distribute the product yourself, or do you need the provider to provide distribution?

Here’s how we approach purchasing decisions, keeping in mind that procurement laws vary city to city.

| Buying a large volume | |

|---|---|

| We can distribute ourselves | Try to buy direct—you could save a lot of money!

A single delivery drop, combined with a large-volume order, may be appealing to manufacturers. |

| We need the vendor to distribute | Reach out to both direct suppliers and third-party vendors. You may save money on the product going direct, but you may need to figure out a distribution solution. If the direct vendor can’t distribute, a third-party vendor may be more cost-effective as they are accustomed to managing logistics. |

| Buying a small volume | |

|---|---|

| We can distribute ourselves | Reach out to both direct suppliers and third-party vendors, but don’t bank on the direct vendors. Even if you’re able to manage distribution, direct suppliers typically don’t do business in small volumes. |

| We need the vendor to distribute | A direct supplier probably won’t be interested. We recommend purchasing through a third party. |

Incorporating USDA Foods Entitlement Spending

The USDA purchases food to support the American agricultural market and to remove surplus. These food products are called USDA Foods. These USDA Foods in turn are offered to recipients of different government supported programs, including the National School Lunch Program.

Districts participating in the National School Lunch Program receive an “entitlement” budget of about $0.36 per lunch served. If a district serves 100,000 lunches in a year, the following year they will get $36,000 -- they can use this money to order off a set list of USDA foods, and use that food in their school meal programs.

Key things to know about the USDA foods entitlement:

Use it or lose it: any money left unspent at the end of the year is lost, it does not roll over

Shopping off the USDA foods list can be a strategic way to get high quality product at a lower price than the commercial market

Types of food include fruits, vegetables, meats, cheese, beans, peanut products, rice, pasta products, flour and other grains - get the full list here: USDA Foods in Schools Product Information Sheets

How do I maximize the entitlement?

Figure out which commodity products align with your nutritional standards. Many groups choose to avoid so-called “brown box” items. These are generic products (chicken strips, whole grain flour, etc.) that must meet some specifications, but are not narrowly regulated. As a result, brown box products can vary in quality, ingredients, shape, size, etc., and must be purchased “sight-unseen”—meaning you can’t see what you actually get until after you’ve paid for it.

Compare the commodity prices with market prices to get the maximum value from the food program. Just because the item is available for purchase doesn’t mean you’re getting the best value. For example, a case of beef might cost $100 on the commodity market, but only $85 from a commercial vendor. While it may be tempting to think of the commodity allowance as “free money” and use it without cross-shopping, in this example you would end up paying 17% more for beef using commodity dollars as compared with commercial.

Learn more:

Webinar: Managing USDA Foods for Schools Entitlement, Orders, and Inventories in SY 2021-2022

Creating the ideal customer experience

There are many ways to build a kitchen, from a minimal set up with warming ovens to a full commercial commissary kitchen. The approach outlined here is based on our experience with Boston Public Schools.

A good place to start is considering the customer experience. We think it’s important to have food served in a cafeteria setting, as close as possible to the kitchen, where students can choose their own meals.

Three important considerations that inform your kitchen design:

Menu: What kind of food do you want to serve, and how? Deciding that we wanted to serve deconstructed food, similar to a fast-casual restaurant, gave us a sense of the kind of equipment we needed (and didn’t need) to prepare and serve.

Space considerations: Some schools have 400’ kitchens, and it’s important to be able to replicate the model in these buildings, despite their small footprint. You may be able to create cafeteria space from under-utilized rooms.

Food delivery options: The more frequent your food deliveries, the less storage space you need. Consider how frequently you can get food delivered - and what more frequent deliveries will do to food costs - to determine how much storage space you need. Weekly deliveries will require more storage space than daily or 3x weekly deliveries.

Construction budget: Plumbing and extensive renovation can be expensive, quickly. Scope your projects carefully beforehand to determine a realistic construction budget.

Discovering the Finishing Kitchen

Knowing that we wanted to serve a deconstructed concept, but being realistic about space and equipment expenses, we turned to an industry success story for inspiration: build-your-own-bowl fast casual restaurants like Sweetgreen and Chipotle.

We liked how fast-casual restaurants served a limited number of simply-prepared ingredients that customers could choose to create any number of customized meals, and had kitchens that typically occupied a small footprint in an urban area. Speaking with culinary experts familiar with the fast-casual model lead to two main insights:

The first insight was the idea of a finishing kitchen. In many school districts the prevailing definition of “kitchens” meant full-service commercial kitchens with a wide array of specialized (and expensive) industrial cooking equipment like griddles, tilt skillets, stand-up mixers, and gas ranges. While many districts are fortunate to have full-service kitchens, we learned from the fast-casual experts that a so-called “finishing kitchen” could meet the needs for most food service operations. Finishing kitchens are perfect for preparing, cooking, and assembling food in a small space; rather than having a full suite of equipment, finishing kitchens have the essentials to prepare whole, real food from scratch.

The second insight was to serve a deconstructed menu from a hot and cold service line. The fast-casual experience taught us to use sauces and dressings to extend menu variety while keeping our ingredient list manageable. And, a deconstructed model maximizes customer choice while simultaneously allowing the kitchen to be efficient in reducing food waste and managing inventory.

Planning for Kitchen Renovations

We strongly recommend breaking down the renovation process into manageable steps. We worked on a scale of 1-4 to describe the level of difficulty of construction and expected budget range at a school site. 1 was the easiest (simple equipment swap, for example)—and 4 was the hardest (walls to be built or removed, plumbing work to be done, etc.).

The truth is: thinking about renovations and capital work can be a bit overwhelming. But there are 3 quick steps to help best determine the scope of work:

Hold a walk-through with relevant teams. Gather a group to do a walk-through of the kitchen space. Our groups included of the following members:

The facilities team from the school or district; these people know the buildings best and can weigh in on the level of difficulty. It’s important to include someone who knows where the drains are in the building as this is the least flexible part of construction.

A senior leader from the school, like a principal/headmaster, or director of operations. Making decisions with them will save a lot of back and forth and possible extra construction later on.

If resources allow, having an architect along for the walk-throughs can also be of benefit.

Rate each individual school kitchen according to the scale above. We found it helpful to categorize each kitchen on our 1-4 scale based on anticipated difficulty of renovations—and then plan construction according to these levels, working within the existing infrastructure as much as possible. This helps set expectations for the entire team, and gives people a better understanding of the scope of the project.

Set a plan. We found that projects deemed to be a 3 or 4 difficult level would require an architect to complete, while those deemed a 1 or 2 could usually be managed by the district’s facilities team. Once you know what level you’re working at—and with what kind of team you’re working—you can put a detailed plan into motion as soon as possible.

Tips for kitchen construction

Plan kitchen construction for the summer months when school is not in session. You’ll want to work with school leaders who might need to alter or cancel summer programs that use the school spaces that will be under construction.

Plan for construction taking longer than expected. As with all things in life, you can’t guarantee that everything will go according to plan. Give yourself some wiggle room and some contingency plans should things go over schedule.

Bundle construction or equipment procurement for multiple schools in your bidding/RFP process, rather than bidding out one job at a time. We found that it was crucial to capitalize on the economy of scale.

Visit kitchens that support programs you would like to emulate—this could be at a school, community center, restaurant, or any operation that you admire. Talk to as many people as you can about what works (and doesn’t work) for them.

Examples

Don’t Have Space to Build a Kitchen? Think Again!

The My Way Café team receives a lot of questions from other districts who are interested

in replicating the My Way Café model. One of the most common questions is from schools wondering how to build a kitchen when space is extremely limited. We ran into this problem in many of our buildings, and in every case we found the space to make it work. Here are a few examples of kitchens we squeezed into tight quarters—all are fully functional My Way Café sites, cooking and serving fresh food to students every day.

Kitchen Design

EXAMPLE 1: Adams Elementary

Prior to My Way Café, Samuel Adams Elementary had a small space with a refrigerator, freezer, milk chest, and warming oven. We knew we could fit a kitchen in this space with some creativity, so we moved the fridge and freezer to the opposite wall, removed the stairs, and installed a Combi oven, hot & cold serving lines, hot-hold warmer, 3-bay sink, and produce sink. There is a cafeteria immediately outside the kitchen where students eat after choosing their food off the line.

EXAMPLE 2: Patrick J. Kennedy Elementary

At the Patrick J. Kennedy school, the former kitchen space housed a fridge and freezer, desks, milk chest, and a warming oven. We installed produce and dishwashing sinks, a Combi oven, a new fridge and freezer, and hot and cold service lines. We also built a wall to frame the kitchen and create separate space for storage.

Data collection is critical to the success of any food business – and school food is no exception. A strong food program needs to understand how food and money move through the food service ecosystem, and you’ll need software to track this.

Here are some things software can track:

What did we order from our vendors?

What did we receive?

What did we ship to each school?

How much food was produced, served, and discarded at each site? What are our projections for future food purchasing?

Which employees are staying on top of their paperwork? (This information can help area managers coach employees and continuously improve the operations of the system.)

How much are we spending on food at each site?

Food & Nutrition Services Software Landscape

The food & nutrition team must select a software company from the list of USDA-approved vendors. There is a wide range of products, services, and prices available—and because the shopping process can be overwhelming without a strategy, we feel it’s important to take a guided approach to understand if vendors can meet your needs.

Key Components of Your Software

Before purchasing software, be sure to fully understand the needs of your new food service program. In essence, software manages the flow of food (and therefore money) through the food service program. And, you will use the software to generate deliverables (worksheets, re- ports, etc.) to support operations at various points in the process. Your software must be able to manage these moving parts and generate reports/worksheets in a flexible way to meet your business needs.

Key considerations for your software search:

Production records collected digitally

Inventory tracking: Tracking food inventory is important, so the software must be able to record in multiple locations to account for warehouse and site inventory.

Units of measure: Software must have flexible units of measure in recipes, warehousing, inventory, and ordering from vendors to account for different ways we measure products.

Cloud-based vs. server-based: Cloud-based software is preferable for many reasons—flexibility, better backup, automatic updates, no hardware costs, real-time data, flexible reporting, etc.

Point of sale hardware: This does not need to come from the same provider as your software system if you’re transitioning over time, but long-term it makes sense to use a unified system. POS hardware is often a big incremental price bump, as it’s usually the only piece of hardware the system requires. If you are purchasing a POS, consider a mobile option (for grab & go carts).

Price: This is variable depending on the type of system you purchase, how the vendor charges for customization, and how modular the system is. Some systems allow you to pick and choose the features, and only pay for the functionality needed. Some enterprise systems come as an entire platform and don’t allow you to cherry pick what you need (read: you have to pay for functionality you don’t need). Carefully review the packages and pricing to make sure you’re not overpaying for products you don’t need.

Remember: Procuring software—like procuring food—may be subject to your city’s procurement laws if you’re purchasing for a public district.

Technology

Staffing a scratch kitchen – or transitioning from unitized meals to scratch cooking – can mean a significant change in staffing and training.

This transition won’t happen overnight: your team will need to put a lot of time into figuring out an ideal staffing model, designing a training curriculum, and developing employees on the job. One thing to keep in mind: kitchen employees may belong to the AFSCME union, so any decisions around labor must comply with union regulations.

Staffing Model

The staffing in many schools is tied to the number of serving lines in each kitchen. For context, we estimate that one serving line (hot bar + cold bar + point-of-sale) is needed for every 400 students that eat lunch at a school. Every serving line requires one employee serving on the hot line, a second employee serving on the cold line, and a third employee monitoring point-of-sale. This means we need a minimum of three staff for every 400 students served.

Regardless of school size, every kitchen has a full-time manager, and the remaining staff work a combination of full- and part-time shifts. Beyond this basic measure, consider other data points (including meals per labor hour, discussed below) to calculate staffing at each individual school.

Even if we don’t know exactly what staffing will look like at every school prior to launch, we can use the number of stu- dents eating lunch at a school to predict our labor needs (and costs) as we scale—understanding, of course, that there will be additional staff needed in some situations.

Staffing and Training

MPLH is an important statistic in many cities with a unionized labor force. Meals per labor hour is calculated by adding up the total meals served at a school per day, and dividing by the total employee hours worked per day. Many districts have fixed MPLH standards based on the age group of the school.

We mention this because, while we sometimes make observations that a school seems over- or under-staffed, there are often MPLH factors at play that restrict our ability to change staffing at a given school. If your district has MPLH agreements, it may be important to factor these into your labor model.

Training

Many larger districts, like Boston, choose to employ an all-star team of Chef Trainers. Chef Trainers are professional chefs with specific expertise in coaching culinary teams. Chef Trainers support kitchens, and managers in particular, with all aspects of running the kitchen.

In the example of Boston Public Schools, the Chef Trainers were a relatively late addition to the team–as the program grew, the need for culinary training expertise became amplified. Chef Trainers provide an enormous amount of value to the program, and we strongly recommend districts consider a similar role to support kitchens in transition.

Staff are typically trained in two ways: On-the-job experience, and during staff meet- ings. We recommend that your district come up with your own training based off of your district calendar and training needs.

Tip! Engage the local culinary community. Many local chefs and culinary professionals will gladly volunteer to help train new employees, develop training curriculum, and provide technical manager training in kitchen ops.

Using several different methods, the kitchen teams will need to be trained on a variety of topics. At a high- level, here are some of the most important categories to consider:

Your school’s food service values (service with a smile, offer food rather than pre-plating without student choice, etc.)

Point-of-sale and meal accountability

Food safety

Equipment operation, including cooking technique (knife skills, baking, etc.)

Projecting food needs and placing accurate orders

Software (receiving & placing orders, production records, inventory, etc.)

Targeted leadership training for kitchen managers

The Boston Public Schools team operated on a 3-week cycle to onboarding the new scratch-cooking kitchens, which launched 2 at a time over the course of several years.

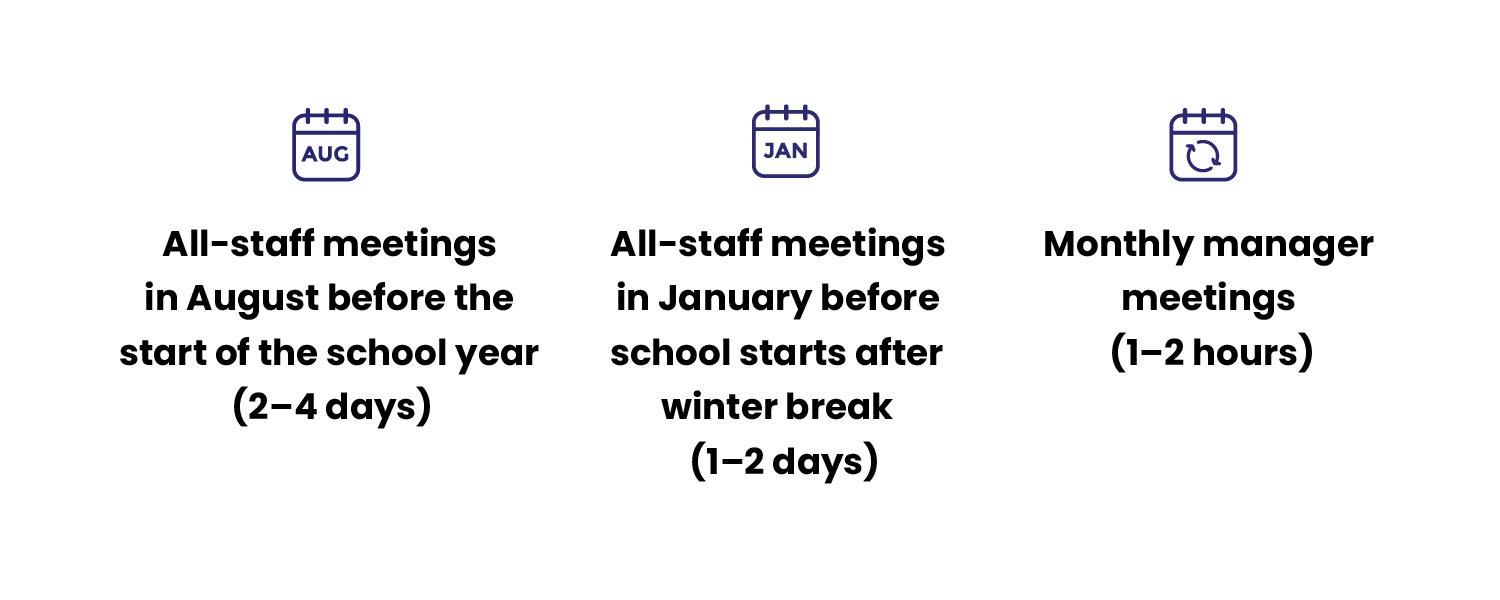

In addition to staff training during the rollout, all staff attend professional development throughout the year. Here’s an example schedule:

A note on hiring

Maintaining fully staffed kitchens, and a healthy pool of subs in the case of absences, is essential for kitchen operations. Hiring and staffing can be a challenge: like many other cities, food service workers are in high demand. This, paired with low unemployment numbers nationwide, means that BPS can struggle to maintain a robust hiring pipeline.

Recommendation: build a detailed model for the hiring funnel. It is critical to understand how the top of the funnel (“How many people do we need to apply for each job”) converts to the bottom (“How many people do we need to hire”?). Collecting data on every stage of the hiring process will reduce unexpected labor shortages.

Creating a brand for a school meals program can be an important part of a successful transformation. Read on to learn about our experience in the Boston Public Schools as a case study for other communities.

Why brand a school food program?

From the beginning, we knew that creating a strong brand would be critical to the success of My Way Café. Branding would help people understand the values My Way Café stands for—and would help create a common language for Boston to talk about the new program.

When the My Way Café team initially launched the four pilot schools in East Boston, people were excited—there was a lot of buzz about the new program. Parents, students, school leaders, community members, and local organizations/nonprofits were beginning to talk about how school food was changing in Boston. Our team was thrilled that the program was gaining traction—and we wanted to create a great name that would not only focus the conversation around our program but also give parents something specific to ask for when advocating for food changes at their schools.

Challenge

In Boston, like many other large urban districts, innovation can be challenging. Even the most popular ideas can lose momentum as time erodes the public sense of urgency. Because My Way Cafés launch on a staggered schedule over the course of several years—not all at once—there are some schools that will have had My Way Café for 4+ years by the time new schools come on board. The My Way Café team faced a challenge: How do we drive awareness and maintain excitement among parents, principals, and students during the multi-year rollout period?

In addition to maintaining momentum, the My Way Café team needed to find a way to differentiate the new program from the two other existing food service models in the district (cafeteria and satellite). Stakeholder groups did not have a common way of speaking about the food programs, and we wanted to eliminate confusion and distinguish My Way Café from the legacy programs.

Insights

As we found early on with the East Boston pilot, the new food program we were championing was compelling and easy to talk about. All the positive feedback and reception gave the program a concentrated buzz around one, singular idea. So, luckily, we didn’t have to start from scratch. The My Way Café team learned from consumer products marketing: Marketers create raving fans by packaging and productizing offerings, and then by staying true to the brand identity as products evolve over time.

Solution

We picked the name My Way Café to represent choice for students—which is one of the most important values of the program. My Way Café offers signifi-cantly more choice than the other two Boston Public Schools food service mod-els, and we wanted that to be represented clearly in the name.

After naming our program My Way Café, we developed a brand vision and collateral, including:

Logo, color scheme, and brand “look & feel”

Website with resources for parents, kitchen managers, and the public

Banners and signs for cafeteria spaces Multilingual picture cards for the serving lines

Uniforms for Chef Trainers

My Way Café core value statements Marketing materials for principals to use with parents during launch

Pre-roll out meetings with principals to help set expectations and support their communications with students, staff, and families

Along with our new brand, we developed an earned media strategy designed to engage local reporters to cover My Way Café and help us spread awareness about school food change. We knew that lots of families and local organizations cared about how Boston feeds kids—and getting the word out across different media channels helped share the My Way Café story quickly and efficiently.

Results

The team built a beautiful, recognizable, and consistent brand for My Way Café that created a shared language for fans and supporters of the program. Parents, students, and school leaders are now able to ask for My Way Café by name at school committee meetings. At schools that already participate, school leaders are building programming around My Way Café—using the brand across different channels (social, email marketing, print) to advertise events and generate excitement. Other organizations have been leveraging the branding, too. FoodCorps, for example, uses the branding in their city-wide work to increase food access.